Living in South Africa has a numbing effect on a human being. One soon becomes almost unaware of the daily cycle of violence, destruction, and death. Reports of children being mowed down by gunfire wash away before ones eyes — they are numbers, statistics. Getting acclimatized to trauma is a very human way of ensuring that we do not go insane. Yet in spite of this numbness, some events are so startling in their sheer senselessness that they can awaken even the most hardened of hearts from that stupor.

The first time I saw him was through a haze of red-and-purple fog as I struggled to retain consciousness while being wheeled through the casualty ward of Johannesburg's Coronation Hospital. White coats and anonymous voices whipped about me in dizzying slow motion. And then, through the haze, a face appeared, smiled. A hand appeared, and clasped mine.

"Hello, Kanthan," the voice said. "I'm Abu Asvat."

I'd met him before, though never in person. As a black political journalist in South Africa, my beat — like that of many of my colleagues — was never as clearly defined as those of our more-famous international counterparts. And it had been while researching emergency medical facilities available to victims of police brutality in the township that I had come across the name of this strangely anonymous hero of Soweto. In telephone conversations, Dr. Abu-Baker Asvat turned out to be rather uncomfortable in attempting to define his personal involvement, and it took glowing testimonials from his more overtly-political friends and acquaintances before the picture began to emerge.

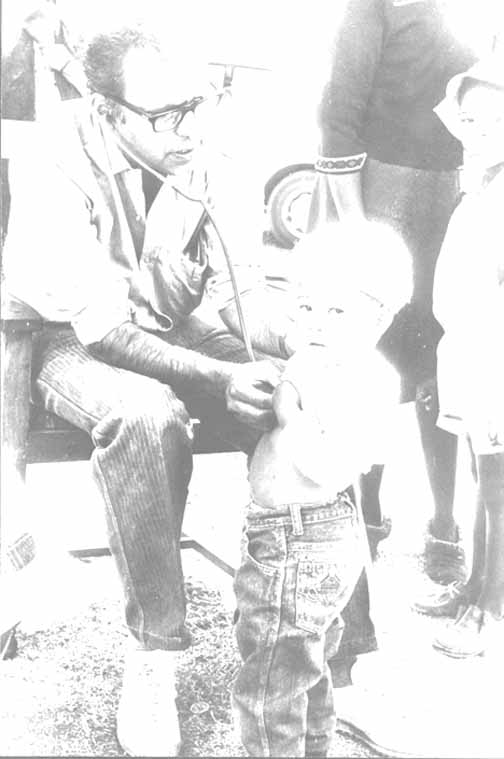

Dr. Asvat was chairman of the Health Secretariat of the Azanian People's Organization, a body formed to carry on the ideas and initiatives first proposed by Steve Biko who had been murdered in police custody in 1977. Living in the township of Lenasia near Johannesburg, he commuted daily to neighbouring Soweto where he ran his practice, dispensing free care frequently and providing comfort and cheer to victims of apartheid's brutality; be it the direct brutality of gunshot wounds, or the more subtle brutality of legislated poverty. Coordinating teams of volunteers, Dr. Asvat frequently led mobile clinics into the more isolated sections of black South Africa providing medical facilities in areas where such treatment was otherwise unobtainable, and the nearest hospital inaccessible to those without private transportation.

Now, as his voice shook me out of my anesthetized stupor, I heard myself responding in a voice that sounded much too normal to be my own. "Hi Abu. I told you we'd be meeting sometime soon. You guys have to get me out of here. I'm supposed to be swimming this weekend..."

He chuckled, a warm hearty chuckle, and said: "I'm just visiting, but it looks like you're not going to be swimming this weekend. Maybe the week after?"

It was six weeks later that I saw him again. As I lay propped up in bed with traction pins and pulleys stretching my rather messily-broken right femur into some semblance of normality, he wandered over to my bedside, dressed in one of those badly-fitting hospital robes. "I didn't get to go swimming yet," I told him.

"Neither did I," he said. "I'm a patient here right now."

We spoke only briefly of the small kidney stone that was bothering him before launching into an animated discussion on the State of the Nation. Over a month in the crowded public ward of Coronation with a short-wave radio as my only real source of information had left me starving, and I greedily lapped up every scrap, every tidbit relating to the world of politics outside. I badgered him for news about the formation of the United Democratic Front, a body that was to be launched that evening in Cape Town. The UDF's politics were significantly different from Dr. Asvat's own beliefs, but he was rather optimistic about the formation of the anti-Apartheid body.

"It will give them (the government) another headache," he said.

He smiled as the newsreader announced that Albertina Sisulu had been named as one of the organisation's three presidents. Mrs. Sisulu, as wife of the imprisoned secretary-general of the banned African National Congress, had been silenced for many years by the State. The law prohibiting her from appearing in public places had prevented her from working in any public hospital as a nurse — her profession. Questions of political disagreement had not been on Dr. Asvat's mind when he employed Mrs. Sisulu in his Soweto practice. It was a similar attitude that led him to Brandfort in the Orange Free State where Winnie Mandela, wife of the world's most famous political prisoner, had been banished by the State. The clinic established by Dr. Asvat soon gained international prominence as a glowing example of the selfless dedication of Mrs. Mandela. Dr. Asvat, as usual, remained silent about his role.

He left the hospital soon after that August of 1983, fully recovered from the treatment for his kidney stone. I followed some weeks later with plaster-encased leg and bruised ego back into the newsroom. In the years that followed up to the present, as the situation in the townships worsened, Dr. Asvat's role became even more important. The frequency of victims of tear-gas inhalation, whippings, and gunshots increased. Along with this came new forms of trauma — "improved" rubber bullets that killed, internal injuries from overt torture during incarceration, and more.

Dr. Abu-Baker Asvat died last week. On Friday, two men entered his surgery in Soweto asking for treatment. Mrs. Sisulu entered their names into the register, and one of the men signed his name, while the other affixed his thumbprint, saying he could not write. When they were admitted into the surgery, one of the men drew a firearm. Dr. Asvat was shot twice through the heart. The men fled.

Living in South Africa has a numbing effect on a human being. One soon becomes almost unaware of the daily cycle of violence, destruction, and death. Reports of children being mowed down by gunfire wash away before ones eyes — they are numbers, statistics. Getting acclimatized to trauma is a very human way of ensuring that we do not go insane. Yet in spite of this numbness, some events are so startling in their sheer senselessness that they can awaken even the most hardened of hearts from that stupor.

Dr. Asvat's death was one of these. His murder was clearly an assassination, yet it would be pointless to ask "why" or "who". The men who killed him were not professionals — practiced killers would never have signed their names and left their thumbprint, let alone kill in front of a witness and leave the witness unharmed. The apartheid system's brutality twists and contorts the most innocent of human beings to the extent that many people would pick up a gun and fire it at an unknown person in exchange for a paltry sum that would ensure their existence for another week while the real killers will tuck away their wallets and go about their work with nothing present to ever link them to their crime. There is no justice that we may call for. No trial, prison sentence, execution will ever make up for the sheer waste of human potential, for in killing Dr. Asvat, they have also murdered countless others who will no longer have him to depend on to save their lives. There is no immediate target upon which we can heap our anger, our grief, our frustration.

In the insanity that is today's world, there is not much that one can say in praise of people who every day through sheer necessity commit countless acts of heroism. In a country that does not permit its population to aspire to much, one can hope, at best, to become a truly exceptional human being.

Dr. Asvat was a truly exceptional human being. No finer tribute can be paid to him. He would not have asked for more.