How we deal with death is as important as how we deal with life...

Picture a modern-day Rip van Winkle, rising from slumber in the area north of Pretoria. He walks down the N1 as that superhighway broadens into eight lanes. Night falls, and he shields his eyes in terror as a glittering carpet of light rises from the ground to blot out the moon and stars.

Gauteng, the place of gold. Africa's powerhouse is a triumphant shout of defiance against the forces of the gods who in millennia past boiled and crushed the earth to create and imprison the metal that men have fought and died for.

First with picks and shovels, then with the thunder of dynamite, the earth has yielded to the incessant demand.

Rolling plains have been reshaped into hills and dales. Dry scrubland has been turned into a green paradise as mighty rivers have been stripped of their power that this land may bloom.

Johannesburg, for all the crime and squalor, is truly magnificent — a modern day Aladdin has rubbed the golden lamp and built a palace overnight.

I left Durban for Johannesburg little over a year ago, and loved it. The simple pleasure of buying a dozen second-hand books from a street vendor and paying with three coins. The larger pleasure of meeting diplomats, leaders, the rich and would-be rich, the beautiful, the talented, or those who thought themselves to be any of these. This is, after all, Africa's true capital.

And my father, who had lived in that city for 19 years, got to know and love his granddaughter...

"I'm leaving Johannesburg," I told him. "I'm moving to Cape Town. I start work there on the first of October."

"If you do that," he replied, "I've got nothing left to live for."

He had been in and out of hospital during the year gone by. Decades of smoking had resulted in a chronic blockage of his right coronary artery. A bypass was recommended, but he would not consider the operation.

"It's one of the safest operations today," I pleaded with him. He would not hear of it. Placed on a regimen of drugs to thin his blood and ease the pressure on his heart, his health still declined.

Hours before I was to board a plane for Cape Town for a meeting, he collapsed. I rushed to meet the ambulance at the hospital where he was readmitted. After I was sure that he was comfortable, I left for the airport.

When I returned two days later, he was much improved and cheerful. A further two days later, he relapsed.

"Take me out of here," he pleaded. "My time has come."

"I can't," I told him. "The drip is keeping you alive. You just need a few more days, and I'll be able to take you away, back down to Durban."

It was the last time he was fully conscious. The next day, on doctors' advice, I called in the family.

Over the next few days, a stream of friends and relatives poured in from around the country. But his smile was for his granddaughter. "Hello Aura, my darling," he said to her before lapsing into unconsciousness again.

And on August 31, while the world recoiled from news of another's death, he died with a smile.

I still ask myself "what if?" It's a futile act and I force myself to bury it.

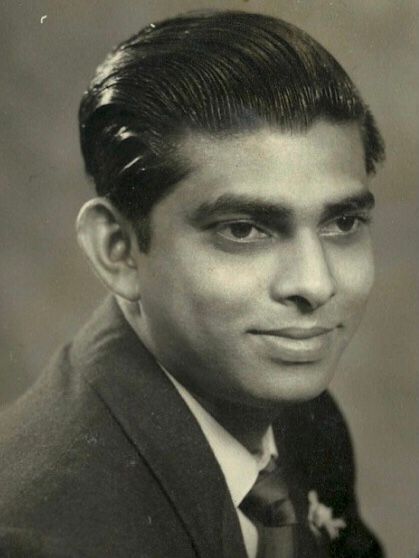

Strangely, now that he's gone, I feel closer to him than I have been for years. The road to Cape Town, the very same N1, stretches before me, and I hold a gift from the place of gold — a moment 30 years past snatched from time in defiance of the gods and forever preserved on a circle of gold.

From my compact disk player, his golden voice fills the air. He lives on. And I smile as I brush away the tears.