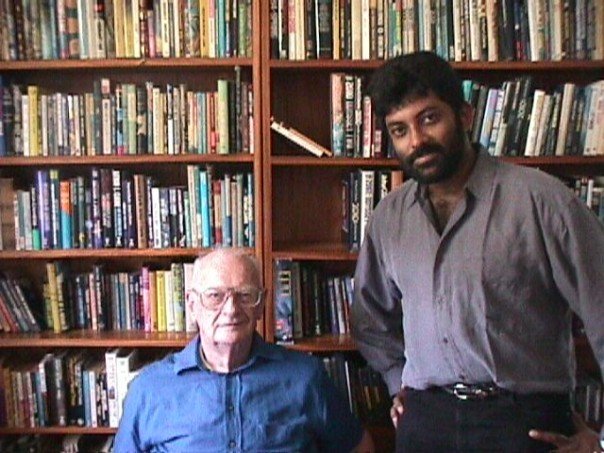

Arthur C Clarke at his home in Colombo, Sri Lanka

"Having done several thousand interviews in all media, I'm now completely fed up with talking (even about myself). Everything anyone needs to know will be found in my own writings…"

IT'S a sweltering day in what is definitely one of the most beautiful places in the known universe. Three-wheeled taxis — "auto-rickshaws" — weave in an out of traffic at a blistering pace. My companion, Earl Joseph — a magazine journalist based in Gauteng — shuts his eyes and clutches his seat tightly as a 20-ton behemoth careens directly towards us. I laugh as our driver flings us out of the path of the oncoming truck back onto the "legal" side of the road.

Twenty minutes later, we enter a foyer wrapped in a moonscape and from there up the stairs into his secretary's office. The walls here are lined top to bottom with framed certificates of awards, degrees, honours, fellowships — far too many to count or note before his secretary ushers us in.

The man who no longer gives interviews looks up from behind his desk where he sits in a wheelchair, gazing out at us with Yoda-like eyes from behind thick glasses. He is catching up on his email.

"I did a search once on the Internet for sites referring to me which found about 25 000, so I gave up," he says as he wheels himself around and shakes hands.

Uncharacteristically, I find myself tongue-tied.

Arthur Charles Clarke was born in Minehead, England in 1917. While just a 28-year-old Royal Air Force radar officer in 1945, at a time when space travel did not exist, Clarke developed and published the theory of communication satellites -- devices in geosynchronous orbit that could relay information around the world.

Today, it's hard to think of any invention that has had a greater impact on global politics. Communication satellites — most of them occupying what is now called the Clarke Orbit — have given us international telecommunications, CNN, MTV, the ability for doctors to perform long-distance surgery, the ability for me to transfer these words from my laptop computer back home to any part of the world ... All of which should qualify him for a nomination for Man of the Millennium.

None of this existed when, as a nine- or ten-year-old, I heard a radio dramatisation of "The Sands of Mars" and found myself entranced. I entered my teens with a huge collection of science fiction in my possession, and could rattle off verbatim extracts from Asimov, Blish, Clarke, Dick ... But the scientific acuity of Clarke's writing set him apart from the willing suspension of disbelief required for the works of others.

Twenty years ago, when I discovered he lived in Sri Lanka, I cajoled a girlfriend (who lived in Colombo) into getting me his autograph. (I still have the autograph; haven't a clue what happened to the girlfriend…)

Two decades on, and I find myself for the first time in Sri Lanka — as a guest of the Kumaratunga government on a fact-finding mission. It seemed really silly to try, but I still picked up the phone and called the number listed in the directory.

And he answered.

Why Sri Lanka? The man who has charted outer space in his mind has a fascination with inner space. Since 1954, his interest in underwater exploration has taken him to the great barrier reef of Australia and the Indian Ocean, and he now shares that with the world through the Colombo-based Underwater Safaris.

Afflicted by Post Polio Syndrome in 1984, Clarke now requires daily physiotherapy. He can no longer walk unaided and needs a wheelchair to move any distance. In spite of this, he still scuba-dives on Indian Ocean wrecks, plays table-tennis (he holds the edge of the table), watches the moon through his 14-inch telescope, and plays with his Chihuahua "Pepsi" and his six computers.

And he still works a 10 hour day. "Greetings, Carbon-based Bipeds!" will be released through St Martins Press later this year. He's completed 52 episodes of ACC's Mysterious Universe for the Discovery Channel, and the millennial edition of 2001, a space odyssey. The list goes on and on ...

We chatter aimlessly… About the sky over Cape Town and the Southern Hemisphere view of the stars; about dealing with volumes of electronic mail; about the digital camera I use to get a picture of us together.

And all too suddenly, it's time for his next meeting. And we leave.

"Where did you go to?" diplomatic affairs writer Jean-Jacques Cornish asks us when we get back to the group.

"Think of it as a pilgrimmage," says Earl.