October 1999. I was Managing Editor of the Cape Times. Under my tenure, the paper had turned a profit for the first time in a decade.

And I found myself sitting across the desk from Shaun Johnson who had recently taken over from Rory Wilson as Managing Director of Independent Newspapers Cape.

"Shaun," I said to him. "This is the third year that I am drawing up budgets for the Cape Times, and this is the third year that I am being asked to make cutbacks. At what point does this stop? At what point do we reinvest in journalism?"

"We don't," he said.

"Well Shaun," said I, "By my reckoning, I still have about 25 years of working life ahead of me. I need to be in a business that's growing, not cutting back."

I handed in my resignation the following day.

Print journalism was my first love. My first byline was in October of 1980 after being expelled from the University of Durban-Westville just over 30 years ago; having been taught the basics of WWWWWH and the inverted pyramid by Farook Khan.

At the time of my leaving the country at age 24 with the 1986 State of Emergency, I was political reporter for Post as well as working a 12-hour shift every Saturday at the Sunday Tribune as Branch Correspondent feeding the then Sunday Star.

My mentors were Ameen Akhalwaya, Vas Soni, Quraysh Patel. My editors were Dennis Pather at Post and Ian Wyllie at the Sunday Tribune. All of these gentlemen were extraordinary wordsmiths with passionate commitment to freedom of information. Ameen and Dennis were both Nieman Fellows. Vas and Quraysh were lawyers who did not practise because they would not swear allegiance to the apartheid state – a then prerequisite for admission as an attorney.

When I returned to the country in March 1994 ahead of the elections, I once again took up my old Saturday seat at the Sunday Tribune, now as revise sub-editor.

The Tribune was still at the forefront of excellence in journalism. The resonance of the cry "You are Tutsi!" which signalled the death sentence for unfortunate hundreds of thousands of Rwandans was amplified with brutal gravitas in double page spreads, leaving us with no choice but to pay attention.

The internecine violence in Natal ahead of our first democratic elections, which left hardly any rural family untouched, was reported on with dispassionate sympathy. Even on election day, amid reports of ANC volunteers taken hostage and shot in the back at Ulundi, the Tribune did not give in to hysteria.

Journalism in the new South Africa, it seemed at the time, was in good shape.

Then the rot began to set in.

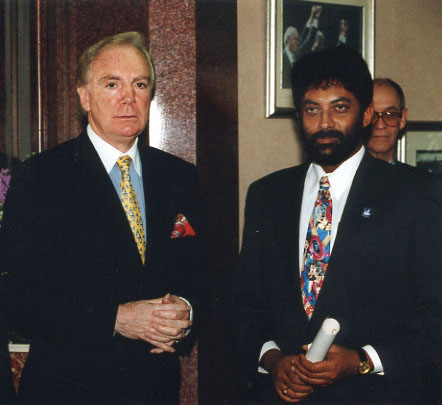

Sir Anthony J F o'Reilly arrived in our country, fêting our beloved president, Nelson Mandela. O'Reilly had his eye on the Argus Company. He promised many things – training and development of a new cadre of black editors, the appointment of an international advisory board, and a partridge in a pear tree. Madiba was clearly smitten. Hands were shaken. Controlling interest in the Argus Company changed hands for around R300-million. There was speculation within the company that this was less than Caxton's Terry Moolman had been prepared to pay.

At first, there was an overall sense of excitement at the Irish invasion. The launch of Business Report as a new national financial daily (it's a supplement, dammit!) was celebrated with pomp and splendour.

Seven promising "young" editors-in-training were trotted out with fawning fanfare to spend time at Harvard Business School and at Harvard's Nieman Foundation in preparation for our anticipated leadership roles. (The seven were Mathatha Tsedu, Ryland Fisher, Esther Waugh, Kaizer Nyatsumba, Dennis Cruywagen, Rich Mkhondo, and me.)

But while there was much window dressing at the upper echelons of the company, a systematic denuding began at the lower levels. First major casualty was the Argus Cadet School – which for many years had been the finest in-house journalism training programme in the country. That disappeared quietly. (I hired Motshidisi Mokwena from the last class of 96-97 to work at the Cape Times.)

Then came the downgrading of positions. The Argus Company had made extensive use of the Patterson grading system used by many large organisations. (A simplistic overview – the lowest paid unskilled worker would be A1, the MD would be E5.) Most editors were in the E band with assistant editors in the D band. New policy was that positions would be filled at lower bands (and therefore lower salaries and benefits) than before.

And then came the culling of positions. The word "retrenchment" was never used, but vacant positions were frozen and then made redundant. "We need to sweat our assets," were the words of then CEO Ivan Fallon.

Then came the culling of editions. The afternoon papers in the group (Star, Daily News, Argus) used to produce four editions every day -- Stop Press, City Late, Final, and Late Final. In addition, editors were able to "slip" changes during the print run (most commonly to correct typos or spelling errors). The front page lead would inevitably change between editions.

Then came the reduction in the number of pages of the newspapers. Yes, you could take a 32 page main body, reduce it to 24 pages, and charge the same amount of money for it. As a consequence, you had reduced print costs, and needed fewer journalists to fill the pages. At the Cape Times, this resulted in the ridiculous decision to drop horseracing pages from the sports section and fire the racing editor – the result being that sales of The Citizen shot up on race days.

I had the first of many arguments with then MD of Independent Newspapers Cape, Rory Wilson, at an exec meeting where he berated our editorial team for losing readership to Die Burger. My response was to place both papers side by side on the table. Die Burger was four times as thick as the Cape Times and at a lower price.

"How do you expect us to compete when you keep cutting back on the space to tell stories and the resources to produce them?" I asked. "You're just going to have to produce better quality stories than Die Burger," he said.

Today, newspapers in the stable are shadows of their former self, with notable exceptions of Post and Isolezwe that have managed to grow circulation, bucking world trends.

Iqbal Surve, through broad based empowerment vehicle Sekunjalo, now stands poised to take back our media heritage.

I have only one piece of advice for him – reinstate the Argus Cadet School.

There has never been a greater need for young enquiring minds that are committed to the future of this country to be trained in how to tell the South African story.

Accurately.

Objectively.

Fairly.